User:OrenBochman/My Media Copyright

This is an assignment for Simone's adoption program. You are welcome to edit this page if you notice any errors or have any additional information to add, but as a courtesy, please notify OrenBochman if you make any major changes to avoid any possible confusion between him and his adoptee(s). Thanks! |

Copyright for Commons

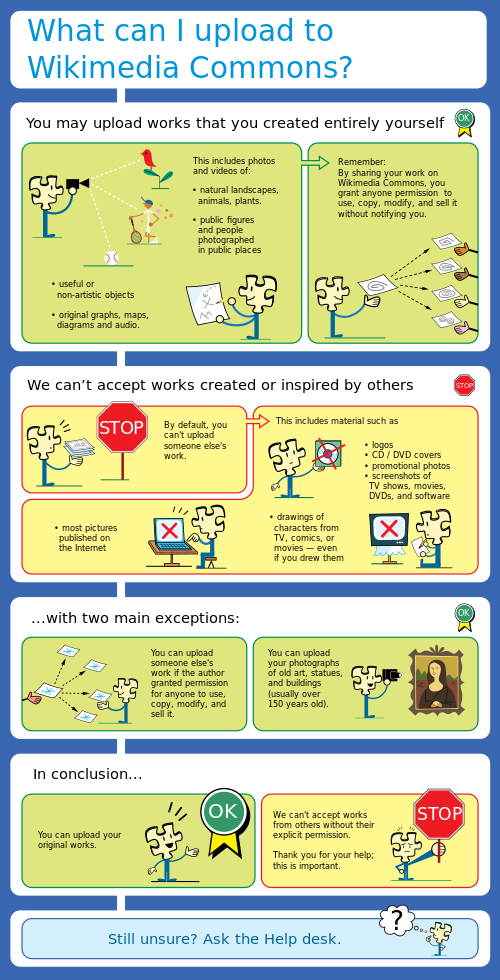

editWikimedia Commons accepts only free content, that is, images and other media files that can be used by anyone, anytime, for any purpose. The use may be restricted by issues not related to copyright, though, see Commons:Non-copyright restrictions, and the license may demand some special measures. There is also certain material, the copyrights of which have expired in one country while still applying in another. Some of the details are explained below. Wikimedia Commons tries to ensure that any such restrictions are mentioned on the image description page; however, it is the responsibility of reusers to ensure that the use of the media is according to the license and violates no applicable law.

Wikimedia Commons accepts only media

- that are explicitly freely licensed, or

- that are in the public domain in at least the United States and in the source country of the work.

Wikimedia Commons does not accept fair use justifications: see Commons:fair use. Media licensed under non-commercial only licenses are not accepted as well.

The license that applies to an image or media file must be indicated clearly on the file description page using a copyright tag. All information required by that license must be provided on the description page. The information given on the description page should be sufficient to allow others to verify the license status. It would be best to do this immediately in the summary field on the upload form.

If you request permission from a copyright holder, please use the email template to do so. |}

Acceptable licenses

editA copyright license is a formal permission stating who may use a copyrighted work and how they may use it. A license can only be granted by the copyright holder, which is usually the author (photographer, painter or similar).

All copyrighted material on Commons must be licensed under a free license that specifically and irrevocably allows anyone to use the material for any purpose; simply writing that "the material may be used freely by anyone" or similar isn't sufficient. In particular, the license must meet the following conditions:

- Republication and distribution must be allowed.

- Publication of derivative work must be allowed.

- Commercial use of the work must be allowed.

- The license must be perpetual (non-expiring) and non-revocable.

- Acknowledgment of all authors/contributors of a work may be required.

- Publication of derivative work under the same license may be required.

- For digital distribution, use of open file formats free of digital restrictions management (DRM) may be required.

The following restrictions must not apply to the image or other media file:

- Use by Wikimedia only (the only non-free-licensed exceptions hosted here are Wikimedia logos and other designs which are copyrighted by the Wikimedia Foundation).[1]

- Noncommercial/Educational use only.

- Use under fair use only.

- Notification of the creator required, rather than requested, for all or for some uses.

For example, the following are generally not allowed:

- Screenshots of software that is itself not under a free license. However, screenshots of software under the GPL or a similar free software license are generally considered to be OK. See Commons:Screenshots.

- TV/DVD/Videogame screenshots. See Commons:Screenshots.

- Scans or reproductive photographs of copyrighted artwork, especially book covers, album/CD covers, etc. See Commons:Derivative works.

- Copyrighted symbols, logos, etc. (Not to be confused with trademarks.)

- Models, masks, toys, and other objects which represent a copyrighted work, such as a cartoon or movie character (rather than just a particular actor, regardless of a specific role). See Commons:Derivative works.

Commons also allows works that are not protected by copyright (i.e. works in the public domain). Please read the section about public domain below.

For an explanation of the justification for this licensing policy, see Commons:Licensing/Justifications.

Multi-licensing

editYou can offer as many licenses for a file as you want as long as at least one of them meets the criteria for free licenses above. For example, files under a "non-commercial" license are OK only if they are at the same time also released under a free license that allows commercial use.

Multi-Licensing with restrictive licenses may be desirable for compatibility with the licensing scheme of other projects; also, multi-licensing allows people who create derivative work to release that work under a restrictive license only, if they wish—that is, it gives creators of derivative works more freedom with regards to which license they may use for their work.

Well-known licenses

editThe following well-known licenses are preferred for materials on Commons:

- Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike licenses

- GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

- GNU General Public License (GPL) / GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL)

- Free Art License

- Open Data Commons, for freely licensed databases where the contents are also free or available under a free license or cannot be separated from the database [1].

Again, works in the public domain are also accepted (see below). See Commons:Copyright tags for more licenses.

Note: The GFDL is not practical for photos and short texts, especially for printed media, because it requires that they be published along with the full text of the license. Thus, it is preferable to publish the work with a dual license, adding to the GFDL a license that permits use of the photo or text easily; a Creative Commons license, for example. Also, do not use the GPL and LGPL licenses as the only license for your own works if it can be avoided, as they are not really suitable for anything but software.

Works which are not available under a license which meets the Definition of Free Cultural Works are explicitly not allowed. See the Wikimedia Foundation board resolution on licensing for more information.

Some examples of licensing statuses commonly found on the Internet, but forbidden on Commons, include:

- Creative Commons Non-Commercial Only (-NC) licenses

- Creative Commons No-Derivatives (-ND) licenses

- Unlicensed material only usable under fair use, fair dealing, or other similar legal exceptions (see below for the reasons)

Non-permitted licenses may only be used on Commons if the work is multi-licensed under at least one permitted license.

License information

editAll description pages on Commons must indicate clearly under which license the materials were published, and must contain the information required by the license (author, etc.) and should also contain information sufficient for others to verify the license status even when not required by the license itself or by copyright laws.

Specifically, the following information must be given on the description page, regardless if the license requires it or not:

- The License that applies to the material. This should be done using a copyright tag.

- The Source of the material. If the uploader is the author, this should be stated explicitly. (e.g. "Created by uploader", "Self-made", "Own work", etc.) Otherwise, please include a web link or a complete citation if possible. Note: Things like "Transferred from Wikipedia" are generally not considered a valid source unless that is where it was originally published. The primary source should be provided.

- The Author/Creator of the image or media file. For media that are considered to be in the public domain because the copyright has expired, the date of death of the author may also be crucial (see the section about public domain material below). A generic license template which implies that the uploader is the copyright holder (e.g. {{PD-self}}) is no substitution for this requirement. The only exceptions to this is if the author wishes to remain anonymous or in certain cases where the author is unknown but enough information exists to show the work is truly in the public domain (such as the date of creation/publication).

Of less importance, but should always be provided if possible:

- The Description of the image or media file. What is it of? How was it created?

- The Date and place of creation. For media that are considered to be in the public domain because the copyright has expired, the date of creation may be crucial (see the section about public domain material below).

These points of the description can be done at best using the Information template. For usage of this template see Commons:First steps/Quality and description.

Scope of licensing

editIn some cases, a document (media file) may have multiple aspects that can and have to be licensed: Every person that contributed a critical part of the work has rights to the results, and all have to make their contribution available under a free license—see derivative work. However, the distinctions are unclear and may differ from country to country. Here are a few examples to clarify:

- For a music recording, the following aspects must be taken into account, and each must be under a free license (or in the public domain):

- The score of the music (rights by the composer)

- The lyrics of the song (rights by the writer)

- The performance (rights by the performers)

- The recording (rights by the technical personnel / recording company)

- For a picture of artwork (also book covers and the like), it is similar:

- The creator of the original artwork has rights to any reproductions and derivative work.

- The photographer has rights to the image, if it is not a plain reproduction of the original.

- For a picture of a building, note that the architect may hold some rights if distinct architectural features are shown, but see also Commons:Freedom of panorama.

This is often problematic, if the artwork is not the primary content of the image or is not clearly recognizable: in that case, usually only the creator of the resulting picture (recording, etc.) holds a copyright. For instance, when taking a photograph of a group of people in a museum, the photo may also show some paintings on the walls. In that case the copyright of those paintings does not have to be taken into account. The distinction however is not very clear.

Note that the license for all aspects has to be determined and mentioned explicitly.

Also note that reproductions usually may not be copyrighted; the creator of an image of a picture owns no copyright to the resulting digital image. The only relevant copyright is that of the original picture. This also applies to Screenshots.

Material in the public domain

editCommons accepts material that is in the public domain, that is, documents that are not eligible to copyright or for which the copyright has expired. But the "public domain" is complicated; copyright laws vary between countries, and thus a work may be in the public domain in one country, but still be copyrighted in another country. There are international treaties such as the Berne Convention that set some minimum standards, but individual countries are free to go beyond these minimums. A general rule of thumb is that if the creator of a work has been dead for more than 70 years, his works are in the public domain in the country the creator was a citizen of and in the country where the work was first published. If the work is anonymous or a collaborative work (e.g. an encyclopedia), it is typically in the public domain 70 years after the date of the first publication.

Many countries use such a copyright term of 70 years. A notable exception is the U.S. Due to historical circumstances, the U.S. has more complex rules. In the United States, copyright generally lasts:

- for works first published before 1978: until 95 years after the first publication, and

- for works first published 1978 or later: until 70 years after the author's death, or for anonymous works or work made for hire, until the shorter of 95 years since the first publication or 120 years since the creation of the work.

- Works published before 1923 are in the public domain.

For works created before 1978 but only published 1978 or later, there are some special rules. These terms apply in the U.S. also for foreign works.

However, the year and location of publication is essential. In several countries, material published before a certain year is in the public domain. In the U.S. this date is January 1, 1923. Furthermore, in some countries all material published by the government is public domain, while others claim some copyrights, yet others are very restrictive (see country specific details below).

In some jurisdictions (like the United States), one can also explicitly donate work one has created oneself to the public domain. In other places (like the European Union) this is technically not possible, but one can grant the right to use the picture freely with, for example, the Creative Commons Zero Waiver, which waives all rights granted by copyright.

See also the Hirtle chart, that can help you determine if something is in the public domain in the United States.

Interaction of United States copyright law and non-US copyright law

editCommons is an international project, but its servers are located in the U.S., and its content should be maximally reusable. Uploads of non-U.S. works are normally allowed only if the work is either in the public domain or covered by a valid free license in both the U.S. and the country of origin of the work. The "country of origin" of a work is generally the country where the work was first published.

When uploading material from a country outside the U.S., the copyright laws of that country and the U.S. normally apply. If material that has been saved from a third-party website is uploaded to Commons, the copyright laws of the U.S., the country of residence of the uploader, and the country of location of the web servers of the website apply. Thus, any licence to use the material should apply in all relevant jurisdictions; if the material is in the public domain, it must normally be in the public domain in all these jurisdictions (plus in the country of origin of the work) for it to be allowable on Commons.

For example, if a person in the UK uploads a picture that has been saved off a French website to the Commons server, the upload must be covered by UK, French and US copyright law. For a photograph to be acceptable for upload to Commons, it must be public domain in France, the UK and the US, or there must be an acceptable copyright license for the photograph that covers the UK, US and France.

Exception: Faithful reproductions of two-dimensional works of art, such as paintings, which are in the public domain are an exception to this rule. In July 2008, following a statement clarifying WMF policy, Commons voted to the effect that all such photographs are accepted as public domain regardless of country of origin, and tagged with a warning. For details, see Commons:Policy on photographs of old pictures.

Uruguay Round Agreements Act

editThe Uruguay Round Agreements Act or URAA is a US law that restored copyrights in the U.S. on foreign works if that work was still copyrighted in the foreign source country on the URAA date. This URAA date was January 1, 1996 for most countries. This means that foreign works became copyrighted in the U.S. even if they had been in the public domain in the U.S. before the URAA date. See also Wikipedia:Non-U.S. copyrights.

Because the constitutionality of this law was challenged in court, Commons initially permitted users to upload images that would have been public domain in the U.S. but for the URAA. However, the constitutionality of the URAA was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Golan v. Holder. After discussion, it was determined that the affected files would not be deleted en masse but reviewed individually. There was further discussion about the best method for review of affected files, resulting in the creation of Commons:WikiProject Public Domain.

Fair use material is not allowed on Commons

editWikimedia Commons does not accept fair use content. See Commons:Fair use.

Derivative works

editYou want a picture of Mickey Mouse, but of course you can't just scan it in. Why not take a picture of a little action figure and then upload it? Don't. The reason why you can't upload photographs of such figures is that they are considered as derivative works. Such works can't be published without permission of the original creator.

The US Copyright Act of 1976, Section 101, says: "A derivative work is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a “derivative work”." A photograph of a copyrighted item is considered a derivative work in US jurisdiction. US Copyright Act of 1976, Section 106: "(...) The owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following: (...) (2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work;"

Therefore, "unauthorized" derivative works, like photographs of copyrighted action figures, toys, etc., must be deleted.

For more information, see Commons:Derivative works.

Simple design

editRegarding trademarks (see also Commons:Image casebook#Trademarks): Most commercial items and products are protected by intellectual property laws in one way or another, but copyright is only one such protection. It is important to make the distinction between copyright, trademarks, and patents. Wikimedia Commons generally only enforces copyright restrictions, for these reasons:

- Almost anything can be trademarked, and it wouldn't make sense to forbid everything.

- Trademarks and industrial designs restrictions are pertinent to industrial reproduction, but photographs of such items can otherwise be freely reproduced.

→ For these reasons Commons accepts any trademark whose copyright has expired. Moreover, Commons accepts images of text in a general typeface and of simple geometric shapes, even if it happens to be a recent trademarked logo, on the grounds that such an image is not sufficiently creative to attract copyright protection.[2] Such images should be tagged with {{PD-ineligible}} or one of the list of more specific tags for this kind of works (e.g. {{PD-textlogo}} for simple logos).

It is often very difficult to determine whether a design is protected by copyright or not, and images of these sorts are frequently nominated for deletion, with various results. See Commons:Threshold of originality and/or “Threshold of originality” (in Wikipedia) for some guidance.

Fonts

editThe raster rendering of a font (or typeface) is not subject to copyright in the U.S., and therefore is in the public domain. It may be copyrighted in other countries (see intellectual property of typefaces on Wikipedia). You should use {{PD-font}} in this case.

Checklist

editLet's assume you took a picture with your camera, or you've scanned it from somewhere, or you've downloaded it off a web server - and want to upload it to Wikimedia Commons. How do you know what's OK and what's not? Here's a simple chart that helps you decide. In cases of doubt, read the further advice for your country first. If you still don't know for sure, ask on Commons:Help desk or Commons:Village pump in your local language.

See Commons:Image casebook for a more complete list.

OK

editYour own photos of:

- Nature (forest, sky, etc.)

- Animals (cats, dogs, etc.)

- Insects (ants, beetles, etc.)

- Produce (apples, tomatoes, etc.)

- People who have given their consent for their image to be published

- You (as long as you don't use this as your private webspace), but not pictures others took of you (these require the consent from whoever took the picture)

- Objects that are public domain by age both in the United States and your jurisdiction:

- Buildings built by an architect who died 70+ (preferably 100+) years ago

- Works of art created by an artist who died 70+ (preferably 100+) years ago and first published before 1923

- Books by authors who died 70+ (preferably 100+) years ago and first published before 1923

- Newspapers and Magazines published by an author who died 70+ (preferably 100+) years ago and first published before 1923

Own scans of:

- Material where copyright has expired in both your jurisdiction and the United States.

- Pictures created entirely by you (based either on no earlier source or on a source which is in the public domain)

Material from web servers:

- Material where copyright has expired in your jurisdiction, the United States and the jurisdiction of the web server.

Questionable, may or may not be OK

editAll kinds of copyrighted material, when uploader does not own the copyright:

- Logos (only very simple designs are OK, see Simple design)

- Screenshots (see Commons:Screenshots)

Photographs, drawings, scans and other reproductions of:

- Cars (cars with only one color and without any ads, paintings etc. are OK)

- Products of daily use (simple designs are OK)

- Book covers (only very simple designs are OK)

- Currency (depends on country law; please see Commons:Currency)

- Buildings built by an architect who died less than 70 years ago (or is still alive) (see Freedom of panorama)

- Permanently installed works of art in a public place, created by an artist who died less than 70 years ago (or is still alive) (see Freedom of panorama)

- Interiors of private houses, homes, museums

- Celebrities (see Commons:Photographs_of_identifiable_people)

- Normal people who have not given their consent (see Commons:Photographs_of_identifiable_people)

- Pictures of you taken by a third party (Normally ok if it's a candid or casual shot made on your request. Formal or professional snapshots require a formal release. Also subject Commons:Project scope restrictions on how many you may upload)

not OK

edit- Fair use images (see Commons:Fair use)

- Fan art that closely resembles copyrighted material (see Commons:Fan art)

- Reproductions of objects that are copyrighted by someone other than you, like the following:

- Action figures, statuettes and other copyrighted material (see Commons:Derivative works)

- Album, videogame, movie and other commercial products covers, posters, newspapers and magazines whose copyright has not expired (covers and interiors).

- Sounds of things that are copyrighted by someone other than you, like the following:

- Copyrighted radio stations (programs and commercials)

- Lyric songs created by an author whose copyright has not expired

International law

editBerne Convention

editAlmost all countries in the world are party to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (see here for the text). Following this convention, countries enforce copyrights from other countries, according to certain rules. One consequence of these rules is that we should always care about the laws of the country of origin of the work.

Most important is article 7, which sets the term of duration of the protections granted by the Convention. The Convention sets a minimal term of 50 years after the life of the authors (subject to some exceptions). However, each country is free to set longer terms.

- In any case, the term shall be governed by the legislation of the country where protection is claimed; however, unless the legislation of that country otherwise provides, the term shall not exceed the term fixed in the country of origin of the work.

Even though many countries have accepted the rule of the shorter term based on Article 7 of the Convention, please note that the United States Copyright Act has not honored such a rule. For example, 17 U.S.C. 104A(a)(1)(B) may restore copyright on a work published outside the USA for the remaining American copyright term even if its copyright may expire sooner in its source country. This may affect works that were still copyrighted on 1 January 1996 in their source countries. This mean that a work now in the public domain in a Commons user's home country might still be legally copyrighted in the USA. For further details, please visit w:en:Wikipedia:Non-US_copyrights#Dates_of_restoration_and_terms_of_protection for a list of American copyright restoration dates.

European copyright law

editThe European Union has issued directives harmonizing copyright rules in the European Union (see Copyright law of the European Union). Note, however, that directives, unlike European regulations, do not apply uniformly. They have to be transposed into national law by each country's legislature, and they often offer significant leeway in doing so. This is, for instance, the case for the legal exemptions of copyright (equivalent of "fair use"), which are allowed to differ within certain limits.

The most important, for our purposes, is the Directive on harmonizing the term of copyright protection (text). This directive sets the duration of copyright to 70 years following the death of the author (for multiple authors, of the last author; for collective, pseudonymous or anonymous works, following the date of publication).

However, this directive does not shorten already running extended copyright terms in countries that apply them.

The 2001 EUCD, article, 5 specifies exceptions to copyright. However, only one of these exceptions is mandatory (it concerns caching). The others are optional, meaning that for each exception, each country is free to choose whether it adopts it and how it restricts it. Thus, one should not assume that one exception true in one EU country applies in another. Notably, each country is free to chose how to copyright objects permanently located in public places and "simple" photographs.

Finally, there is a considerable amount of case law or jurisprudence on these issues. In some cases, they may create rights or restrictions that do not appear in the text of the law. Thus, one should always be wary in how the law is interpreted in the country of interest, as opposed to merely reading the legal texts.

Country-specific laws

editLaws about copyright differ from country to country. Images uploaded to Commons, unless uploaded from the United States, involve the interaction of two or more copyright jurisdictions. Generally, the policy applied on Commons is to only allow images that can be used in all (or at least most) countries. The laws of individual countries differ especially in the following points:

- The time for which a copyright applies. In most countries, copyright expires no later than 70 years after the death of the author (p.m.a.).

- Status of works of the government. In many (but not all) countries, documents published by the government for official use are in the public domain.

- Material applicable for copyright. In some jurisdictions, pictures of artistic work like architecture, sculptures, clothing etc. can not be used freely without the consent of the creator of the original artwork.

The safest way to apply international copyright law is to consider the laws of all the relevant jurisdictions and then use the most restrictive combination of laws to determine whether something is copyrighted or not. The jurisdictions that might need to be considered are:

- The place where the work was created;

- The place where the work is being uploaded from;

- The place that any web server the work has been downloaded from physically is;

- The United States.

A work is only allowed on Commons if it is either public domain in all relevant jurisdictions or if there is a free licence which applies to the work in all relevant jurisdictions.

In the case of a painting published in France please do apply US-American copyright laws as those copyright laws apply to the servers of Commons. Also apply the copyright laws of the country you are in and the copyright laws of any web server you got the work off. In the case of a French painting uploaded to Commons from a French web server by someone living in the UK three copyright jurisdictions would apply: France, UK and US. US law would mean that if the painting had not been published before 1923 it would be in copyright. British law would mean that if the painting was by an artist who had been dead for less than 70 years it would be in copyright. French law would mean that, if the painting was by an artist who died while in service for France (a concept called Mort pour la France), it would be in copyright for 100 years after the artist's death: an additional 30 years past the term provided by British law. In this case the most restrictive combination of jurisdictions would be French and US. Only if the painting was legally in the public domain in both France and the United States could it be uploaded from a French web server to Commons.

UNESCO has a collection of national copyright laws that should be referred to when creating country-specific tags such as those below.

The Public Domain Calculator by the Europeana Connect project/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek is useful (for people who are not legal newbies) for determining the copyright status of European works in their source nations.

Relevant country-specific differences in the duration of copyright (from 70 years pma) and exceptions of the application of copyright are discussed below (countries are listed in alphabetical order):

United States

editAnything published[3] before January 1, 1923 is in the public domain. Anything published before January 1, 1964 and not renewed is in the public domain (search the renewal records for books and maps here). Anything published before March 1, 1989 with no copyright notice ("©", "Copyright" or "Copr.") plus the year of publication (may be omitted in some cases) plus the copyright owner (or pseudonym) is in the public domain.

Photographic works created after January 1, 1978 are protected for 70 years after the death of the creator. Works created but not published before January 1, 1978 are protected for 95 years from the date they were registered for copyright, or 95 (for anonymous or pseudonymous works) or 120 years (for works by individuals) from year of creation, whichever expires first. (see [2] for more information)

Works by the US Government

editA work by the U.S. federal Government is in the public domain. This applies certainly within the United States; it may, however, not apply in other jurisdictions. See the CENDI Copyright FAQ list, 3.1.7, the U.S. Government's own statement to that effect, but also this discussion.

- Images on government or government agency websites are not necessarily public domain; always look for copyright notices or similar. Especially the images on the favorite website "Astronomy Picture of the Day" are in most cases not within the public domain but copyrighted by their individual authors (so please do not upload images from there to Wikimedia Commons). Images on certain military websites (e.g. AKO) frequently are creations of military members in their individual capacities (e.g. soldiers on patrol using their personal cameras). These images may not be in the public domain, but they are very hard to distinguish from works of military photographers, and they rarely contain copyright information.

- This does not include governments of the individual states. The work of most state and local governments are subject to copyright, but there are exceptions.

- This does not include government-funded corporations like Amtrak or the USPS. In particular, the USPS holds copyright on all US postage stamp designs since 1978 [3] (older US stamps are all public domain).

- This also does not include works commissioned by the US Government, but produced by contractors; in this case, the copyright may have been assigned to the US Government (for instance, the copyright of the official Ada programming language manual was assigned to the US Department of Defense).

- Some US government agencies may work in cooperation with other agencies or corporations; this is in particular the case of NASA, which operates the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in cooperation with Caltech, and operates a number of space projects in cooperation with foreign agencies such as ESA and CNES. Only materials solely produced by NASA will be in the public domain. The other agencies may hold copyright on some material, including material published on NASA sites (there will be copyright notices in that case).

- The government sometimes publishes images with statements about non-copyright restrictions (like the White House photostream). This does not affect copyright.

- Commercial use of some Federal images, such as identifying insignia or identification, is prohibited however. Fraudulent use (such as wearing military decorations without authorization) is also banned. However, restrictions of this nature are not within the scope of Commons policy.

- The United States Army Institute of Heraldry— the official custodian of such images has addressed this issue with its Copyright statement, which informs the reader as to how to meet any commercial needs under this statute.

See also

editNotes

edit- ↑ Debate about these exceptions was discussed at Commons:Alter Wikimedia Commons policy to allow Wikimedia logos, which is now retained for historical reference.

- ↑ See Ets-Hokin v. Skyy Spirits Inc where it was decided that the were not copyrightable

- ↑ For a definition of “publication” see e.g. Copyright Office circular, page 3. This modern definition is only valid for 1978 and later, as the 1909 Copyright Act did not explicitly define it, though the concepts were similar.

External links

editCollections of laws:

- UNESCO collection of copyright laws.

- WIPO Lex.

- CERLALC: Copyright laws of Latin America, the Caribbean states, and Spain and Portugal.

- CIPR: Copyright laws of the CIS nations and the three Baltic states.

- ECAP: Copyright laws of ASEAN countries.

- EuroMed Audiovisual II EU programme; has recent copyright laws of some mediterranean states (from Morocco to Turkey).

Copyright treaties:

- Berne Convention.

- WIPO Copyright treaty.

- EU Council Directive 93/98/EEC on the harmonization of copyright terms in the EU.

Other:

- Circular 38a: International Copyright Relations of the United States, from the U.S. Copyright Office. (A bit dated, some countries are missing.)

- Circular 38b: Highlights of Copyright Amendments Contained in the URAA, from the U.S. Copyright Office.

- 17 USC 104A: Copyright restorations in the U.S. due to the URAA

- Copyright in the USA

Discussion

editAny questions or would you like to take the test? The test is pretty brief...consisting of only three questions! This tutorial gives non-lawyers an overview of complicated copyright laws through an example-based tutorial. It aims to help uploaders decide whether an image or other media file is acceptable on Wikimedia Commons. If you are a re-user looking for information on how to use Commons content in your own work, see Commons:Reusing content outside Wikimedia.