Chapters Dialogue/Project/Methodology/fr

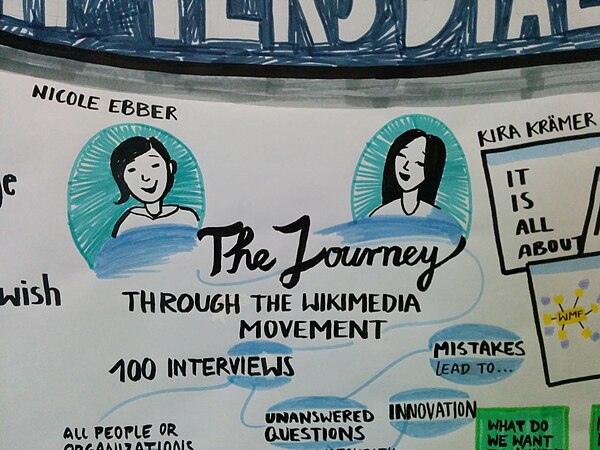

MéthodologieDesign ThinkingThe creation of innovative solutions is complex and challenging, no matter if it is in regard to public services, policies or international relations. As existing waterfall processes are seen as less helpful due to their inflexibility in dealing with emergent or unforeseen circumstances, the need for new approaches to innovation has emerged. The following description is inspired by Ingo Rauth's "Design Thinking: an approach to wicked problem solving in the public sector" (2014). Design was originally developed as a discipline to create new and unexpected outcomes given complex circumstances. While innovation has traditionally focused on technical, engineering based approaches, the problem of developing solutions for a complex and uncertain future poses different challenges. Design Thinking has been studied since the early 1960s, since when it has been argued by management scholars that the way designers think and work could benefit decision makers in dealing with complex problems. But it was not until the early 2000s that a general approach to design (“Design Thinking”) was articulated. In the most general sense, Design Thinking can be described as an approach for human centred innovation. It provides a process framework and toolkit that focuses strongly on the user’s context, values and needs, and takes them as the starting point for the creation of meaningful solutions (products, services, processes, organisational structures etc.). The user perspective can help to provide alignment between diverse teams and organisational departments. First, Design Thinking fosters the strength of collaboration and diversity. A diverse team will bring in different perspectives while thinking about ways to solve the challenge and different techniques support the process of collaborative idea generation. When observations or decisions take place in functional isolation, there is a risk that they will only be based on a fragmented understanding of the problem. In the Design Thinking process, a strong emphasis is on a deep understanding of a challenge in its complexity, before starting to think about possible solutions. The first three phases of Design Thinking are therefore all about understanding the problem: Understand, Observe and Synthesis. Only a profound understanding and precise framing of a (complex) challenge permits the creation of relevant and meaningful solutions in the second half of Design Thinking which consists of the Ideation, Prototyping & Testing and Implementation phases. In this part of the process, the focus lies on the exploration of possible solutions by generating as many ideas as possible, building quick and simple prototypes to make an idea tangible and testing it as early as possible with potential users. The Design Thinking process has an iterative character – it promotes quick learning and improvement in any phase. For example, the feedback in the Testing phase provides learning that deepens the understanding of the problem. This learning can be used either to improve the prototype, or to come up with new ideas, or even to reframe the entire problem statement. This approach can protect organisations from failures that are costly both in terms of time and money. Instead, they can transform themselves into learning organisations that are aligned to the users’ perspective and able to create excellent products, services, strategies and structures. Last but not least there is the toughest part of Design Thinking: bringing a solution to life by implementing it. Implementation is not actually a part of the Design Thinking process, but rather a transition between Design Thinking and classic management: business (or non-profit) strategy, project management and all processes that are necessary to execute the defined strategy goals. Without implementation, even the best ideas won’t have any impact.  Understand and Observe both characterise the research part of the process. Instead of building ideas based on (personal) assumptions, it is valuable to understand the user’s context, behaviour, underlying needs and challenges. Understanding characterises all types of desk research, including setting the framework for the field research and preparing the interviews, observations and immersions. Observing is the field research part, which means interviewing users, observing behaviour, immersion in situations and using cases. The research that takes place in the Design Thinking process is of qualitative nature, while the quantitative part comes into play rather in the implementation phase of an idea. Both types of research are often combined, with, for example a quantitative analysis of the gathered insights from the qualitative research. If Design Thinking is applied in an explorative way in order to gain an understanding of a previous fuzzy problem or poorly defined, not fully understood problem (as opposed to User Testing for an existing product or service) – qualitative research is a valuable tool for that purpose. Qualitative research can be very useful whenever it is necessary to dig into stories and to gain insights in complex situations with different stakeholders. It is a tool that helps to find patterns and contradictions in stories people tell. The research phase is not only about collecting data (in form of stories and insights), but also about building empathy. Listening carefully and being empathic in regard to the personal context of the interviewee, without judgement or prejudice – permits the uncovering of surprising and unexpected stories, aspects and challenges. At the same time, empathy for people and context needs to go hand in hand with rationality to analyse the situation. In addition, considering all relevant stakeholders and their perspectives rather than only touching on isolated aspects of a challenge is of key importance. With an inclusive approach, which means talking to all stakeholders, it is more likely that a “360° view”, which is as little fragmented as possible, will be obtained. Building empathy for all stakeholders and their (often contradictory, opposing) viewpoints, allows for a meta-view of a complex topic. The third phase in the Design Thinking process is Synthesis, which can also be described as problem framing. While Understanding and Observing all about collecting as much information as possible, Synthesis is about narrowing down the amount of information to its “nuggets”. Synthesis means making sense of bits and pieces of information, grouping it into a whole picture and understanding relationships, causes and contradictions. Divergence and problems are often not expressed in a clear statement by users, but rather emerge through opposing ideas, values or requirements. By bringing together information from different sources, it is possible to uncover patterns that are not obvious in the beginning. The process of Synthesis is best supported by visualisation and can include various tools and frameworks, depending on the content, amount of time and goals of the project. The second half of the process is about creating solutions by using different techniques for Idea Generation, Prototyping & Testing and bringing the idea to life through Implementation. Once a precise problem statement has been framed, it is then about Idea Generation: a large number of ideas permits exploration of the different aspects of a problem. A diverse team will bring in different perspectives while thinking about ways to solve the challenge, and different techniques support the process of idea generation. Prototyping & Testing is about translating an idea into something tangible and testing it with potential users. It can be a paper sketch, a role play, a Lego construction, a comic strip or just about anything that helps to explain the core value of an idea. Prototyping helps teams to align the core functions of an idea and to get quick feedback from users in order to learn from it. Users can interact with the prototype, which is far more valuable for feedback than only talking theoretically about an idea. A quick & dirty prototype invites users to review it critically, whereas shiny and “finished” prototypes will mostly receive feedback about their look and usability. As Implementation is not a direct part of the Design Thinking process (yet a crucial factor for Innovation!), we will not go into detail about this topic. Please see theory on Strategic Management and Business Administration for further information. All phases utilise a number of techniques (e.g. brainstorming, storytelling, visualisation) from various disciplines (business development, systemic thinking, service innovation, ethnography, lean software development etc.). Design Thinking can therefore also be considered as a toolbox. It is not a newly invented method, but rather a framework that brings together existing tools and practices and makes use of them in different phases. Rather than strictly following procedures, it is more useful to adapt the principles of Design Thinking to the individual context. Adapting the Design Thinking process to the Chapters Dialogue projectChoix des outils Before starting such a project, it is important to get an idea about the individual culture of the organisation (here: the Wikimedia movement) because, as previously mentioned, all methods or tools need to fit the context. And if the tools don’t work for the project, one needs to “hack” the tools. Kira therefore started by evaluating what kind of Design Thinking practices were relevant for the Chapters Dialogue. The Wikimedia movement is international, with Chapters spread all over the world and run by people with the most varied backgrounds, all operating in highly differing social, economic and cultural systems. Each unique context setting needed to be taken into consideration when trying to create an understanding about the Wikimedia movement. How else could one understand the decisions and behaviour of those local organisations and their stakeholders? We knew that we needed to work with a high level of empathy. This is why we chose to meet as many interviewees as possible personally and to visit them in their environment in order to gain a deep understanding about their work, their aspirations and their challenges. Building trust was a precondition for a fruitful interview and it was important to give each interviewee the space they needed to tell their own individual story. In a movement so complex and diverse, it is only natural that the many opinions of its players are different, some even opposing and contradictory, controversial and emotional. The situation included a large group of organisations and individuals from all over the world, a complex history of the movement and different, interdependent issues and challenges all of them were facing. What was needed most in this situation was clarity. Clarity about the different perceptions, problems and challenges, presented in a frank and open way. It was clear that this project was all about Understanding, Observing and Synthesis of insights. We set the goal of designing and conducting extensive story-based research, interviewing all the Chapters individually. Rather than crunching numbers, we were looking for stories. Qualitative research is best suited to finding patterns and contradictions in stories people tell. In the case of Chapters Dialogue, this was exactly what was needed. The Design Thinking philosophy strongly emphasises empathic skills, which are crucial for any proper field research. Being a good “story collector” means properly listening to people, leading to meaningful insights about their concerns, beliefs and motivation. Combining inside knowledge & outside perspective One crucial aspect of such a project is the combination of inside knowledge and outside perspective. As the topics that we wanted to address were in part highly sensitive and emotional, we needed to approach them in a careful and respectful way. This was only possible by combining knowledge about movement culture, behaviour, rituals, must-haves and no-gos with methodological skills. Having both of these aspects go hand in hand was a key asset for the project. This included:

|

Learn more about

Or go back to know more about

|