Chapters Dialogue/Project/Methodology/nl

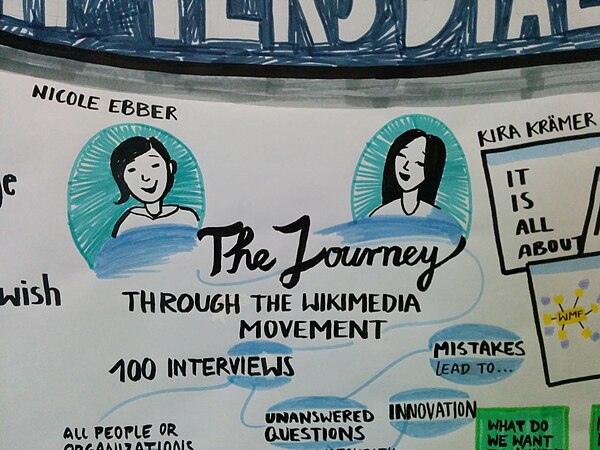

MethodologieDesign ThinkingHet creëren van innovatieve oplossingen is complex en uitdagend, ongeacht of het gaat om openbare diensten, beleid of internationale betrekkingen. Aangezien bestaande watervalprocessen minder nuttig worden gezien als onvoorspelbaar bij het omgaan met nieuwe of onvoorziene omstandigheden, is de noodzaak voor nieuwe benaderingen van innovatie ontstaan. De volgende beschrijving is geïnspireerd op het boek van Ingo Rauth "Design Thinking: an approach to wicked problem solving in the public sector" (2014). Design is oorspronkelijk ontwikkeld als een discipline om nieuwe en onverwachte uitkomsten te creëren onder complexe omstandigheden. Hoewel innovatie van oudsher gericht is op technische, op engineering gebaseerde benaderingen, brengt het probleem van het ontwikkelen van oplossingen voor een complexe en onzekere toekomst andere uitdagingen met zich mee. 'Design Thinking' wordt al sinds het begin van de jaren 1960 bestudeerd, sindsdien wordt door managementwetenschappers betoogd dat de manier waarop ontwerpers denken en werken besluitvormers ten goede kan komen bij het omgaan met complexe problemen. Maar het was pas in het begin van de jaren 2000 dat een algemene benadering van design werd geformuleerd. In de meest algemene zin, kan Design Thinking worden omschreven als een aanpak voor mensgerichte innovatie. Het biedt een proceskader en toolkit die zich sterk richt op de context, waarden en behoeften van de gebruiker, en deze als uitgangspunt neemt voor het creëren van zinvolle oplossingen (producten, diensten, processen, organisatiestructuren etc.). Het gebruikersperspectief kan helpen om afstemming te bieden tussen diverse teams en organisatieafdelingen. Ten eerste bevordert het de kracht van samenwerking en diversiteit. Een divers team zal verschillende perspectieven inbrengen terwijl ze nadenken over manieren om de uitdaging op te lossen en verschillende technieken ondersteunen het proces van het gezamenlijk genereren van ideeën. Wanneer observaties of beslissingen in functionele afzondering plaatsvinden, bestaat het risico dat ze alleen gebaseerd zijn op een gefragmenteerd begrip van het probleem. In het proces ligt een sterke nadruk op een diepgaand begrip van een uitdaging in zijn complexiteit, voordat wordt begonnen na te denken over mogelijke oplossingen. De eerste drie fasen g staan dan ook in het teken van het begrijpen van het probleem: Begrijpen, Observeren en Synthese. Alleen een diepgaand begrip en precieze framing van een (complexe) uitdaging maakt het mogelijk om relevante en zinvolle oplossingen te creëren in de tweede helft, dat bestaat uit de fasen Ideevorming, Prototypering & Testen en Implementatie. In dit deel van het proces ligt de focus op het verkennen van mogelijke oplossingen door zoveel mogelijk ideeën te genereren, snel en eenvoudig prototypes te bouwen om een idee tastbaar te maken en dit zo vroeg mogelijk te testen bij potentiële gebruikers. Het proces heeft een iteratief karakter – het bevordert snel leren en verbeteren in elke fase. De feedback in de testfase zorgt bijvoorbeeld voor leren dat het begrip van het probleem verdiept. Dit leren kan worden gebruikt om het prototype te verbeteren, of om met nieuwe ideeën te komen, of zelfs om de hele probleemstelling te herformuleren. Deze aanpak kan organisaties beschermen tegen mislukkingen die kostbaar zijn, zowel in termen van tijd als geld. In plaats daarvan kunnen ze zichzelf transformeren tot lerende organisaties die zijn afgestemd op het perspectief van de gebruikers en in staat zijn om uitstekende producten, diensten, strategieën en structuren te creëren. Last but not least is er het moeilijkste deel van Design Thinking: een oplossing tot leven brengen door deze te implementeren. Implementatie is eigenlijk geen onderdeel van het proces, maar eerder een overgang tussen Design Thinking en klassiek management: business (of non-profit) strategie, projectmanagement en alle processen die nodig zijn om de gedefinieerde strategiedoelen uit te voeren. Zonder implementatie zullen zelfs de beste ideeën geen impact hebben.  Begrijpen en Observeren kenmerken beide het onderzoeksgedeelte van het proces. In plaats van ideeën te bouwen op basis van (persoonlijke) aannames, is het waardevol om de context, het gedrag, de onderliggende behoeften en uitdagingen van de gebruiker te begrijpen. Begrijpen kenmerkt alle vormen van deskresearch, inclusief het stellen van het kader voor het veldonderzoek en het voorbereiden van de interviews, observaties en onderdompelingen. Observeren is het veldonderzoek, wat betekent het interviewen van gebruikers, het observeren van gedrag, het onderdompelen in situaties en het gebruik van cases. Het onderzoek dat plaatsvindt in het proces is van kwalitatieve aard, terwijl het kwantitatieve deel eerder een rol speelt in de implementatiefase van een idee. Beide soorten onderzoek worden vaak gecombineerd, met bijvoorbeeld een kwantitatieve analyse van de verzamelde inzichten uit het kwalitatieve onderzoek. Als Design Thinking op een exploratieve manier wordt toegepast om inzicht te krijgen in een eerder vaag probleem of een slecht gedefinieerd, niet volledig begrepen probleem (in tegenstelling tot gebruikerstesten voor een bestaand product of dienst) – is kwalitatief onderzoek een waardevol hulpmiddel voor dat doel. Kwalitatief onderzoek kan zeer nuttig zijn wanneer het nodig is om in verhalen te graven en inzichten te krijgen in complexe situaties met verschillende stakeholders. Het is een hulpmiddel dat helpt om patronen en tegenstrijdigheden te vinden in verhalen die mensen vertellen. De onderzoeksfase gaat niet alleen over het verzamelen van data (in de vorm van verhalen en inzichten), maar ook over het opbouwen van empathie. Door goed te luisteren en empathisch te zijn met betrekking tot de persoonlijke context van de geïnterviewde, zonder oordeel of vooroordelen, kunnen verrassende en onverwachte verhalen, aspecten en uitdagingen aan het licht komen. Tegelijkertijd moet empathie voor mensen en context hand in hand gaan met rationaliteit om de situatie te analyseren. Daarnaast is het van cruciaal belang om alle relevante belanghebbenden en hun perspectieven in overweging te nemen in plaats van alleen geïsoleerde aspecten van een uitdaging aan te raken. Met een inclusieve aanpak, wat betekent dat er met alle belanghebbenden wordt gesproken, is de kans groter dat er een "360° view""' Het opbouwen van empathie voor alle belanghebbenden en hun (vaak tegenstrijdige, tegengestelde) standpunten, zorgt voor een meta-view op een complex onderwerp. De derde fase in het proces is Synthese, wat ook wel omschreven kan worden als probleem framing. Terwijl Begrijpen en Observeren alles te maken heeft met het verzamelen van zoveel mogelijk informatie, gaat Synthese over het beperken van de hoeveelheid informatie tot de "goudklompjes". Synthese betekent het begrijpen van stukjes en beetjes informatie, het groeperen ervan in een geheel geheel en het begrijpen van relaties, oorzaken en tegenstrijdigheden. Divergentie en problemen komen vaak niet tot uiting in een duidelijke verklaring van gebruikers, maar ontstaan door tegengestelde ideeën, waarden of eisen. Door informatie uit verschillende bronnen samen te brengen, is het mogelijk om patronen bloot te leggen die in het begin niet voor de hand liggen. Het proces van synthese wordt het best ondersteund door visualisatie en kan verschillende tools en frameworks omvatten, afhankelijk van de inhoud, hoeveelheid tijd en doelen van het project. De andere helft van het proces gaat over het creëren van oplossingen door gebruik te maken van verschillende technieken voor het maken van ideeën, Prototypering & Testen en het tot stand brengen van het idee door middel van implementatie. Als er eenmaal een precieze probleemstelling is geformuleerd, gaat het om maken van ideeën: Een groot aantal ideeën maakt het mogelijk om de verschillende aspecten van een probleem te verkennen. Een divers team zal verschillende perspectieven inbrengen terwijl ze nadenken over manieren om de uitdaging op te lossen, en verschillende technieken ondersteunen het proces van het genereren van ideeën. Prototypering & Testen gaat over het vertalen van een idee naar iets tastbaars en het testen ervan met potentiële gebruikers. Het kan een papieren schets zijn, een rollenspel, een Lego-constructie, een stripverhaal of zo ongeveer alles wat helpt om de kernwaarde van een idee uit te leggen. Prototypen helpen teams om de kernfuncties van een idee op elkaar af te stemmen en snel feedback van gebruikers te krijgen om ervan te leren. Gebruikers kunnen communiceren met het prototype, wat veel waardevoller is voor feedback dan alleen theoretisch over een idee te praten. Een quick & dirty prototype nodigt gebruikers uit om het kritisch te bekijken, terwijl glanzende en "afgewerkte" prototypes meestal feedback krijgen over hun uiterlijk en bruikbaarheid. Omdat Implementatie geen direct onderdeel is van het proces (maar wel een cruciale factor voor innovatie!), zullen we niet in detail ingaan op dit onderwerp. Zie theorie over Strategisch Management en Business Administration voor meer informatie. In alle fasen wordt gebruik gemaakt van een aantal technieken (o.a. brainstormen, storytelling, visualisatie) uit verschillende disciplines (business development, systemisch denken, service innovatie, etnografie, lean software ontwikkeling etc.). Design Thinking kan daarom ook als een gereedschapskist worden beschouwd. Het is geen nieuw uitgevonden methode, maar eerder een raamwerk dat bestaande hulpmiddelen en praktijken samenbrengt en er in verschillende fasen gebruik van maakt. In plaats van strikt procedures te volgen, is het nuttiger om de principes van Design Thinking aan te passen aan de individuele context. Aanpassing van het proces aan het project Chapters DialogueHet kiezen van de hulpmiddelen Voordat u zo'n project begint, is het belangrijk om een idee te krijgen van de individuele cultuur van de organisatie (hier: de Wikimedia-beweging), omdat, zoals eerder vermeld, alle methoden of hulpmiddelen moeten passen in de context. En als de hulpmiddelen niet werken voor het project, moet u de hulpmiddelen hacken. Kira begon daarom met het evalueren van welke vorm van design thinking praktijken relevant waren voor het project. De Wikimedia-beweging is internationaal, met verenigingen verspreid over de hele wereld en beheerd door mensen met de meest uiteenlopende achtergronden, die allemaal actief zijn in zeer verschillende sociale, economische en culturele systemen. Elke unieke context moet in aanmerking worden genomen bij het proberen een begrip te creëren over de Wikimedia-beweging. Hoe anders zou men de beslissingen en het gedrag van deze lokale organisaties en hun belanghebbenden kunnen begrijpen? We wisten dat we met een hoog niveau van empathie moesten werken. Daarom hebben wij ervoor gekozen om zoveel mogelijk interviewers persoonlijk te ontmoeten en hen te bezoeken in hun omgeving om een diepgaande kennis te krijgen van hun werk, hun aspiraties en hun uitdagingen. Het opbouwen van vertrouwen was een voorwaarde voor een vruchtbaar interview en het was belangrijk om elke ondervraagde de ruimte te geven die hij nodig had om zijn eigen individuele verhaal te vertellen. In een beweging die zo complex en divers is, is het natuurlijk dat de vele meningen van de spelers verschillen, sommige zelfs tegenovergestelde en tegenstrijdige, controversiële en emotionele. De situatie omvatte een grote groep organisaties en individuen uit de hele wereld, een complexe geschiedenis van de beweging en verschillende, onderling afhankelijke kwesties en uitdagingen waarmee ze allemaal te maken hadden. Het meest vereiste was duidelijkheid. Duidelijkheid over de verschillende percepties, problemen en uitdagingen, gepresenteerd op een eerlijke en open manier. Het was duidelijk dat dit project alles over het begrijpen, observeren en synthesen van inzichten ging. We stellen ons voor het doel om uitgebreid op verhalen gebaseerd onderzoek te ontwerpen en uit te voeren, waarbij we alle verenigingen individueel ondervragen. In plaats van om te schreeuwen, zochten we naar verhalen. Kwalitatief onderzoek is het beste geschikt om patronen en tegenstrijdigheden te vinden in verhalen die mensen vertellen. In het geval van de dialoog over verenigingen was dit precies wat nodig was. De Design Thinking filosofie legt sterk de nadruk op empathische vaardigheden, die cruciaal zijn voor een goed veldonderzoek. Een goede "verhaalverzamelaar" zijn betekent goed naar mensen luisteren, wat leidt tot zinvolle inzichten over hun zorgen, overtuigingen en motivatie. Het combineren van kennis van binnen en perspectief van buiten Een van de cruciale aspecten van een dergelijk project is de combinatie van kennis van binnen en perspectief van buiten. Omdat de onderwerpen die we wilden behandelen, in sommige gevallen zeer gevoelig en emotioneel waren, moesten we ze op een zorgvuldige en respectvolle manier benaderen. Dit was alleen mogelijk door kennis over bewegingscultuur, gedrag, rituelen, must-haves en no-gos te combineren met methodologische vaardigheden. Het feit dat beide aspecten hand in hand gingen, was een belangrijk punt voor het project. Dit omvatte:

|

Learn more about

Or go back to know more about

|